Richard Corliss: Fulltime Critic

Wednesday | April 29, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

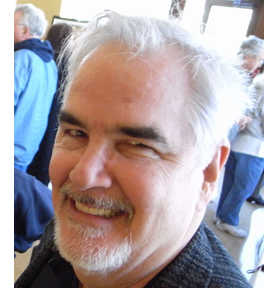

Mary and Richard Corliss, Ebertfest 2008.

DB here:

Parker Tyler called James Agee America’s biggest movie fan, implying that he was a lesser critic for loving movies. But Agee, who was often cast into despair by the films he met week by week, was actually in love with Cinema. From each release he sought glimpses of what he imagined movies could be, and so seldom were.

Tyler’s phrase might better apply to Richard Corliss, but in a deeply complimentary sense. Like his friend and occasional jousting partner Roger Ebert, Richard didn’t judge a film by whether it measured up to some ideal yardstick of the medium. He welcomed the movies—at Time, some 2500, between 1980 and now—as they came. He let his wide tastes, good sense, vast memory and knowledge, and breakneck gift for language decide what they counted for.

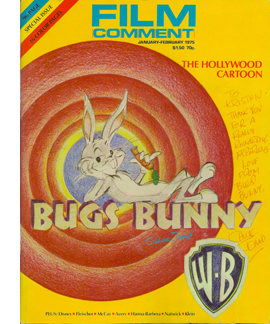

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

When he went over to Time in 1980, that square magazine suddenly looked younger. With Richard joining art critic Robert Hughes, it became a source of lively and penetrating arts journalism. Both turned Timespeak into something fresh. Hughes pulled it toward the eloquent bluntness of the Anglo essay tradition, while Richard transformed the forced puns and slant metaphors into something sprightly. Sarris may have been his mentor, but the rat-tat-tat pileup of clauses (semicolons optional), the self-correcting afterthoughts (as if a nuance had just occurred to the writer), and a concentration on actors all seem to me indebted to Kael. On Edward Scissorhands:

Depp, who wears the hyperalert, slightly wounded expression of someone who has just been slapped out of a deep sleep, brings a wondrous dignity and discipline to Edward. Wiest does a delightful turn on the plucky, loving mothers from old sitcoms. The whole movie, in fact, time-travels between today and the ’50s, when every suburban house could be a quiet riot of coordinated pastels. But the film exists out of time — out of the present cramped time, certainly — in the any-year of a child’s imagination. That child could be the little girl to whom the grandmotherly Ryder tells Edward’s story nearly a lifetime after it took place. Or it could be Burton, a wise child and a wily inventor, who has created one of the brightest, bittersweetest fables of this or any-year.

Richard gloried in the emotional and visceral energy of popular cinema. He defended both porn and zany comedy. On the Big Loud Action Movie he could channel Teenboy patois:

Toward the start of Fast Five — fifth and best in the series that began with The Fast and the Furious in 2001 — Brian (Paul Walker) is in a freight train and Dom (Vin Diesel) is steering a 1966 Corvette Grand Sport alongside it. At the last possible moment before the train goes through a bridge over a river, Brian jumps from the train and lands on the Corvette, which Dom then drives off a, like, million-foot cliff. As the car plummets down the ravine, our guys jump out and land safely in the water.

That “a, like, million-foot cliff” is alone worth the price of the issue. For such reasons, I think that Richard might be the most imitated critic of recent decades. Every reviewer at your town’s weekly hip throwaway wants to write like this.

They mostly can’t. In an essay on Fulltime Killer, Richard compared Johnnie To’s cinematic output to A. J. Liebling’s boast: “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.” It pretty much applied to Richard himself. He wrote about film, books, TV, travel, sports. Of the Bulk Producers we always ask, “When does s/he sleep?” With Richard we have to ask: “When did he pause?”

The Richard I followed most closely was on display in long formats. His book Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974) made a stir that’s hard to appreciate now. Good student of Sarris that he was, Richard was an auteurist. He once tried to persuade me that Russ Meyer was at least as good as Minnelli. Yet his book called us to arms in a different cause.

The most difficult and vital part of a director’s job is to build and sustain the mood indicated in a screenwriter’s script—a function that has been virtually ignored while citics concerned with “visual style” trot off in search of the themes a director is more liable to have filched from his writers. …

When it comes to the mood men, the metteurs-en-scène, auteur critics start tap-dancing away from the subject. George Cukor is a genuine auteur; Michael Curtiz is a happy hack; Mitchell Leisen is actually despised by some critics for “ruining” films like Midnight and Arise My Love. Yet what Leisen and the writers of Hands Across the Table did to make that film the most amiable of thirties screwball comedies is a prime example of sympathetic collaboration. As with so many delightful comedies, it is the writers who create the characters and establish a mood in the first half of the picture, and the director who develops both in the second half. The story line of Hands Across the table isn’t flimsy; it’s downright diaphanous. . . .

Openly imitating Sarris’ catalogue The American Cinema, Richard’s book created an artistic genealogy of screenwriters, picking out the Author-Auteurs, the Stylists, and so on and then ranking them.. But where Sarris is synoptic, Corliss is dissective. Working at full stretch, he gives pages of close attention to particular films. His analyses of The Power and the Glory, The Lady Eve, and The Marrying Kind (“wavering between third-person omniscient and first-person myopic”) carry great intellectual heft, while Sarrisian potshots fly by. Reputations get deflated (Jules Furthman) or elevated (Sidney Buchman).

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

Finally, something I return to often: Richard’s 1990 essay attacking (no politer word will do) TV movie reviewers. “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?” castigates the tribe’s superficiality, their canned brevity, their reliance on clips, and above all their encouraging people to believe in quick judgments. Stars, numbers, grades, and thumbs are too easy. Richard bites Time’s corporate hand, complaining about snack-sized opinions in People and Entertainment Weekly. Against this trend he speaks for longer-form writing, pointing out that Sarris, Kael, and others had their impact because they could surpass the word limits mandated for most reviewers. It takes time to develop ideas that are subtle. Obvious, maybe, but tell that to the young blogger who insisted to me that a review ought to take no more than 100 words.

Roger Ebert was a target of Richard’s piece, and he replied in a courteous counterblast. Yet the men were fast friends. Richard did friendship superbly, with an effusive generosity. Just out of college, I submitted a couple of articles to the new Film Comment, and to my astonishment Richard accepted them. As I turned more academic, I stopped offering pieces to the magazine, but Richard–who could easily have become a film professor himself–didn’t hold it against me. When I came to New York a few years later for a job interview that proved disastrous, Richard and Mary were the only friendly faces I encountered, and lunch at their apartment, larded with gossip, was the high point of that visit.

In later years I encountered Mary, mostly during our visits to MoMA, more than Richard. But every now and then I’d get another burst of gratuitous kindness. He reviewed my Planet Hong Kong in a funny online piece about how Hong Kong film takes the stuffiness out of anybody.

Even a relatively staid critic such as structuralist guru David Bordwell seems to be typing in his shorts, with a beer on his desk.

The last time I saw Richard was with Mary at Ebertfest in 2008. We had a diner breakfast, and Richard did a dead-on imitation of John McCain. I still see that smile—part devilish wise-guy, part nerdy enthusiasm, all glowing good humor. He was wearing goofy trainers bearing the logos of the Majors. They looked damn fine. We had a good day.

In an interview with David Thomson Richard recalls his life and the early Film Comment era. See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensitive appreciation, especially on Corliss’s mastery of the “long reported piece”–another point of contact with Agee.